In tackling corporate tax, we can’t overlook the human side of decision making

‘Business purpose beyond profit’ is a bandwagon in danger of collapsing. It’s no longer voices on the fringe, but the mainstay of capitalism that’s calling for change. Especially after the FT and Economist nailed their colours to their mastheads.

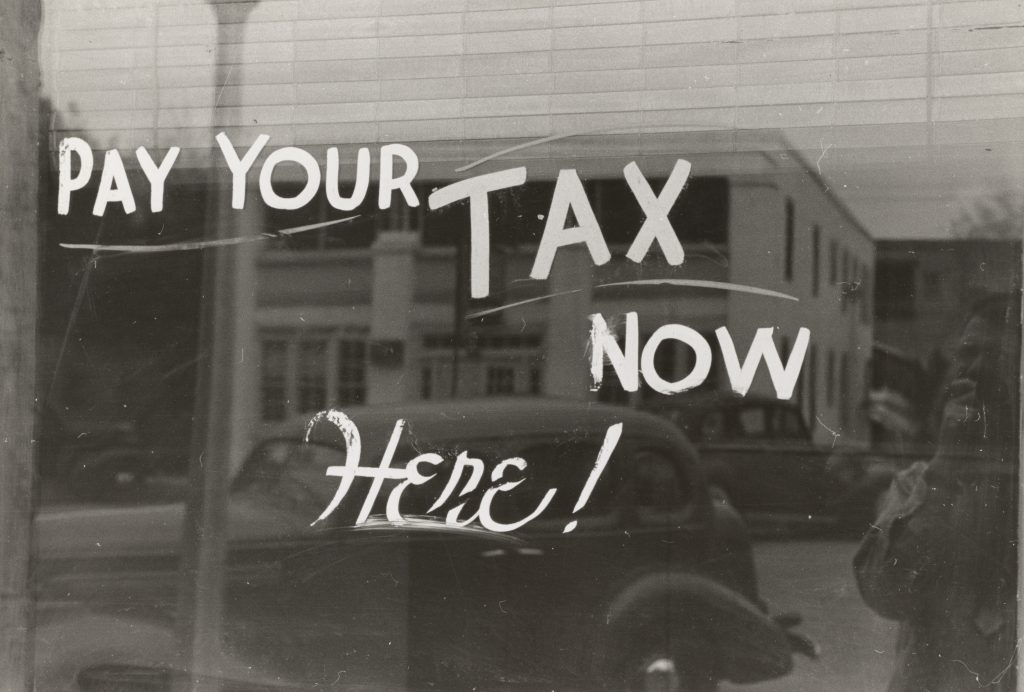

When opinions swing swiftly, reality gets distorted. The voices of the critical experts become even more important in understanding the reality behind the hype. The critical voices have two main arguments; that actions speak louder than words, and the need for systemic, not individual change. These two arguments come alive when you look at tax, the mechanism by which those who live in a society contribute to its functioning, as responsible citizens – the basics.

So, if business is serious about being a force for good, surely it’s covering the basics of paying its fair share of tax?

In the purpose arena, tax rarely gets a look in. People shy away from it because tax is complex and, there’s no nice way to put this, it’s a bit dry. People much prefer the latest shiny innovation that turns carbon into crayons or the hopeful emotions of the latest ad campaign. As a result, basic responsibilities rarely get centre stage.

I’ve spent my 15+ years exploring how business can make more than just money. I started when it when the CBI was lobbying against climate legislation. As the agenda has shifted, so has my work. Moving from sustainability technicalities to changing business cultures, identities behaviours and decisions.

I could hardly call myself a professional in my line of work, however you define it, if I didn’t dive into the tax question. Why have we got here? What stops companies paying their fair share of tax (besides the obvious)? How do tax decisions actually get made?

I’ve had some help along the way understanding the tax system (thank you in particular Loughlin Hickey, Christopher Morgan and Joe Stead for putting up with my questions), the players in it and their perspectives, and the history that’s led us to the current system in all its complex, imperfect, well-meant glory. What follows is an explanation of the situation for the lay person, and a perspective on it from a human decision-making angle. One that’s remarkable in its absence from tax discussions. Let’s go.

We’ve inadvertently built an out of date, overly complicated tax system

Remember, this is broad-brush history. The current tax environment has been built on international rules from the 1920s and influenced by the shift towards a view that business is there to serve its shareholders only, and largely ignore their wider responsibilities as a citizen of society. Business threw the first punch. We’re talking the 80s and early 90s when shareholder primacy ruled and the sentiment of the day, culturally, was becoming more individualistic and materialistic; games where money was the scorecard. Some, many, companies did everything they could to avoid tax, albeit legally. Legislators responded by wielding their pen with greater ferocity. They created more legislations, ramped up the audits. The tax code arms race took off.

Globalisation is both a cause and a solution

Globalisation meant business had ever more options to move their money around to avoid tax. Businesses became hugely influential, with companies in the global tier creating wealth in excess of some countries. Governments found themselves playing a two-track game. Attempting to capture much needed tax revenue through legislation, while trying to capture multi-national investment through tax-reduction initiatives and incentives. No wonder things are messy.

In the late 90’s people started asking questions. By mid the 2000’s there were many more people questioning the status quo. Just because, legally, you could avoid tax, it didn’t mean you should. Then the ‘08 crash and a series of tax scandals broke. Questions were asked at all levels in many countries. Not just technical questions, but ethical and emotional ones. Questions about fairness and responsibility. While all this was happening, the tax codes kept multiplying, companies kept finding new ways to legally avoid paying tax. Then the internet came along and put this complexity on steroids. The Panama Papers and other scandals sparked a steady shift in public opinion. Many countries are now aligned in calling for a consistent approach to digital tax.

The complexity of tax codes, incentives and international accounting practices isn’t something I’m equipped to wrestle with, so I won’t. I can talk about human decision making though, and that’s what all legislation is there to influence. The decisions people make in the name of a specific business.

Decisions, including those about tax, are made by people not legal corporations

In his astoundingly good book, Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari eloquently shows how it’s our ability to cooperate at scale that has enabled our species to dominate every other living thing on the planet. This ability comes from the telling and believing of stories, like the story of the corporation. A corporation is not a real thing. It’s an abstract legal concept. Yet, we’ve become so comfortable with the concept, we’ve forgotten that a business is no more sentient than the orangutan toy my son cuddles at night. A business is controlled by individuals who make decisions, decisions like how much tax to pay, where, when and how.

Bureaucracy won’t solve the problem

Tax isn’t an issue that can be fixed purely by legislation. It would need too many letters to close all the loopholes, and once that was done, quick thinking people will employ new technology to find new ones.

Not realising that tax is a human problem results in an arms race of bureaucracy that benefits no one. As soon as we see it as a human problem, we realise it will never be solved, because humans are fallible and some will always seek to circumvent a widely accepted system for their own personal gain. This means that we are facing an ongoing struggle, a tension that will never be resolved and will always need attention. Recognising this opens a new line of inquiry to find better solutions that will keep the balance in favour of the many.

What does influence our decisions?

We all know that a founding assumption of classical economic theory, that we’re rational actors seeking to maximise our own utility, is largely nonsense. Daniel Kahneman’s work on this won him a Nobel Prize. Incentives are powerful, but they aren’t the whole story. Human decisions are complex things, made up of layers of influence. I’ll skip quite a few, like primal motivations, biology and cultural influences because this would turn into a book. If you do want to read about all that, this series is incredible.

We are going to dig into the layers we can have the most influence over, the layers of social influence. The Milgram experiments famously showed just how far people will go to conform. It’s why Greta stands out so much, because she refuses to follow the herd.

In the social environment, like the physical one, we’re all trying to do what it takes to survive and ideally thrive by doing what gives us status, influence and success. This is an evolutionary thing, because for thousands of years as our species evolved, if you found yourself cast out from the group, you died. Natural selection at work.

We can better understand this social environment by answering three questions. What do people believe is ultimately import, the focus of what we’re here to do? What role does the individual see themselves as playing in this environment? What kind of behaviours and decisions bestow status?

Let’s pick them off, one by one, thinking about the inside of a business when it comes to making tax decisions.

What do people believe we’re here to do?

An old friend works for a big automotive company. Everyone knows their name, but I shouldn’t say it. He runs a big tech team. He’s quite clear about what the business is about, despite its big purpose statement. ‘Making as much money as possible’ he says, ‘that’s what my bosses are measured on, so it’s what they care about.’

Many businesses have statements of purpose. But having one isn’t much more than wallpaper unless it’s embedded in the systems of the business, as my friend’s automotive company proves. As anyone with kids knows, behaviour is a far more powerful form of communication than words. If the business hasn’t invested in changing its systems, including how it manages its data and measures performance to enable people to make decisions to balance short term profit and longer term shared value, nothing will change.

But imagine if a business could do this, could put forward a powerful purpose and provide their tax teams with the information and incentives to consider how their tax decisions could further that purpose in a fair way?

If you consider a statement of purpose to be a statement of the value an organisation creates in the world, then tax becomes another tool to strategically enhance that value creation. Not just a way to meet their legal obligations, or pile up profits at the expense of the education, health and infrastructure of the people whose countries the firm operates in.

This takes us neatly onto the second question.

What role is the individual playing in this environment?

A label is a powerful thing. People spend a lot in therapy to shake them off. Job titles are labels we wear to signify to ourselves and others, what we do and why we matter. A CFO’s job is to control the finances in a way that delivers legislative requirements, maximises profits and reduces costs. A Head of Tax is there to do what exactly? Is the role of the head of tax to pay the least tax? To pay a fair amount of tax? To make sense of very complex laws and make tax a strategic tool for a company? This isn’t about job descriptions, this is about individual identities and sense of responsibilities.

The ICAEW says a career in tax is ‘to help their clients, whether businesses or individuals, to make sure they are meeting their legal obligations.’ Sure, but isn’t that a fairly flat view of what’s possible? How can tax be used to further your own objectives, to make a positive contribution to society in the places the business is best placed to make them?

The Chartered Institute of Taxation says working in tax is ‘a mixture of law, administration and accountancy and it draws on a huge range of intellectual, presentational and personal skills. A tax adviser works with companies and individuals, trying to create the best tax strategies for them.’ It’s a bit better, but is devoid of any form of consciousness, of sentience. A strategy could be to minimise tax payments within the letter of the law. While legally that’s OK, what we’ve already seen is that a purely legal approach to tax isn’t enough.

Tax as a tool for competitive advantage, in a good way?

I’ve already mentioned how tax could be considered as a tool to create more value for the world and therefore the business (provided it can capture its fair share). As awareness of social and environmental issues grow, fuelled by ever faster media cycles and global interconnectedness, and as inequalities become starker, at some point, people are going to start questioning the kind of company they keep.

When it comes to behaviour change, UK customers of Amazon have taught us a valuable lesson. Amazon’s tax contribution to the UK economy, is very small given the size of their revenues here. Many, many people were, to put it politely, upset, by this. But did their ethical stances influence their purchasing decisions? No. Amazon suffered no significant sales decline, despite the significant scale of outrage. Ease of use trumps tax ethics. But as employees, people have much more of their identity wrapped up in the reputation of their employer. Unilever, who make nothing sexier than soap and tea and don’t offer the pay scales of finance, soared to the upper echelons of the world’s most sought after employers as a result of their sustainability work. Facebook has seen its job acceptance rates by software engineer candidates fall from nearly 90% in late 2016 to almost 50% in early 2019, post Cambridge Analytica. Honestly, I’m surprised no one has started to leverage their tax strategy to attract new talent, especially in light of the US, largely tech co. approaches to international tax.

Here, we’re really talking about repositioning tax, taking it into a more nuanced and purposeful space. It means wrestling whole heartedly with concepts of fairness and morality, two concepts that business has typically struggled with and stayed away from. But as the FT and Economist are saying, these things can’t be put off any longer. For tax professionals this should be looked at as an opportunity, because the machines are coming. Automation works best with a set of clear rules and processes and straight forward objectives, which sounds more akin to the definitions of the profession the ICAEW and CIOT talk about.

Yes legislation is essential, as is adhering to principles of responsibility when dealing with these complex codes, but if we don’t wholeheartedly embrace the human aspect too, we’re missing a big part of the puzzle.

The most important contribution tax could make to business and society

Tax is at the real sharp edge of decision making in business. It is a decision with real trade-offs. Does a business structure its affairs to pay less tax in one place so it can pay more in another? How is that decision made? Patagonia’s (the uber purpose pin up co.) is to “Build the best product, cause no unnecessary harm, use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis.” Should they be navigating international tax laws to direct more of their payments to countries whose governments invest more in environmental solutions, or places that are one the front line of environmental decline?

Yes it matters what decisions tax professionals make in their individual businesses, but arguably the most important contribution they could make is in the discussion and debates about the role of business in society, the future of capitalism. After all, the closer to the edge you are, the more you can see, but only if you’re looking for it.

David Willans, Director