Panda Previews: Thames Film by William Raban, (1986)

Every day, our Pandas are committed to working together to create real impact. But outside of work, we all have interests that sometimes link with our day jobs – and sometimes not. We decided to start a new content series, Panda Previews, where one of our Pandas will review a piece of media– be it a documentary, TV show, book, film, or even an art exhibition, to give you a preview into their world and explore why certain media spoke to them. Our first review is by our latest Panda, Jules Moscovici…

I first watched Thames Film during a lockdown film club organised by my best friend. I didn’t think too much of it. Over time, though, it stuck with me. Its rhythm, colour and sound would sit in my mind as I regularly escaped to the riverbanks.

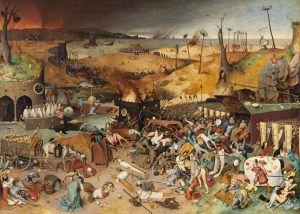

Thames Film is a documentary drawn from footage of a small boat’s voyage from London to Dover, as well as archive video, stills, engravings and recurring paintings such as Brueghel the Elder’s Triumph of Death.

Triumph of Death by Brueghel the Elder (1562)

It is a meditation on the death, time, and transience of the Thames River.

Sound. While the film incorporates opera such as Bach’s St Matthew Passion, its most striking soundtrack is a collage of found recordings (recorded with Richard Guy). For long, hypnotic periods, scenes are cut in parallel with changes in sound. Splashes into the rain, into the low-frequency drones of engines and industry. Dozens of small ships’ horns singing together, coalescing into haunting chords. Seagulls, church bells, and the screams and laughs of a riverside funfair. Just as a repetitive, metallic bang becomes nerve-inducing, it is revealed as a recording of a piling rig. The most beautiful moments are the echoes of ship radars and sonar, sounding like one of the many mixes of the famous Kunta Kinte reggae rhythm.

Raban’s Thames is also a shock of colour. Of blue water, blue skies, grey water, grey skies, reds of rust, greens of moss, flat, blinding sunlight. The river itself is said to be a ‘Strong Brown God’ by narrator John Hurt. A God which Londoners, ‘worshippers of the machine’, have long forgotten as they pour across London Bridge to get to work. Small glances into the water show acknowledgement of its power, cut short by the needs of the city.

The Redsand Towers, built in 1943 by Guy Maunsell. These feature repeatedly in the film.

If Raban insists on remembering the deities and spirituality of water, it is perhaps to allow for space to grieve. In recalling death, the film laments an absence of ceremony, of a funeral. A lack of remembrance for fallen industrial workers, enslaved peoples or the sexual deviants hanged and displayed at Cuckold’s Point (modern-day Rotherhithe). Here, Thames Film becomes a celebration of their lives, their work.

Thames Film is available to stream via Lux for £3.